14ymedio, Rosa Pascual, Madrid, 1 January 2024 — Lea Ypi has not written a book to make friends. Free [Libre], memoirs of the childhood and adolescence of an author who enters adulthood at the same time that her country, Albania, makes the leap to democracy, is a diptych as harsh with the lack of freedoms of the communism of her childhood as with the broken promises of a liberalism that tasted like disappointment. “In 1990 we had nothing but hope. In 1997 we lost that too.”

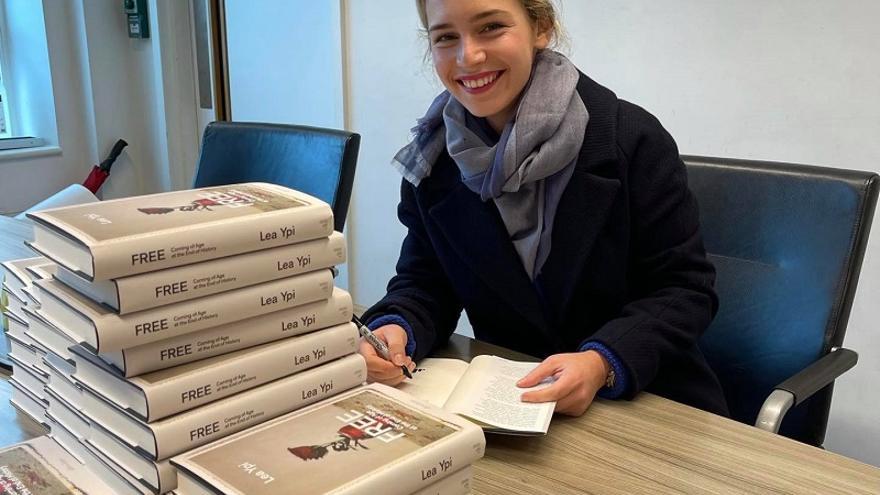

“I never asked myself what freedom meant until the day I hugged Stalin.” With that powerful phrase, which was in all the drafts of the first (and, for now, only) novel by this Albanian born in 1979, the first part of the book unfolds with the subtitle The challenge of growing up at the end of history. The author, a political scientist at the London School of Economics, says that she sat down to write a philosophical essay about the overlap of the concept of the word freedom in communist and liberal societies, but “ideas ended up becoming people.”

Thanks to this turn, Ypi has created a novel that — better than any history book — relates the process of transition of her country from the dictatorship of Enver Hoxa to the rebellion that was about to lead to civil war. The lives – absolutely normal – of her characters, Lea’s family, friends and neighbors, paint a fresco of the daily life of communist society like no essay will.

The first ten chapters of the book are dedicated to this, with scenes in which readers who lived under the same system will soon recognize themselves.

The first ten chapters of the book are dedicated to this, with scenes in which readers who lived under the same system will soon recognize themselves. The lines to do the shopping, the start of classes shouting “pioneers of Enver,” the valuta stores for foreigners – where dreams come true – with their nylon stockings and Bic pens; the empty Coca-Cola can – a memorable chapter to which the book cover makes a nod – as a status symbol…

But, above all, the codes. Little Lea grows up hearing talk at home about how the biographies of her acquaintances had determined their studies, identified with an initial. Although, luckily, most ended up graduating, some ended up expelled. “I’m so sorry, it’s terrible,” is said in those cases. Starting in 1990, she discovered that the letter designated a prison, to be discharged was to be released and expulsion meant death.

Lea grows up in an apparently normal family, with civil servant parents moderately critical of the regime and an intriguing grandmother – the most interesting character in the novel and to whom it is dedicated – who, without being French, speaks French. The propaganda has taken strong root in her and she is, of all those who live in the house, the one who most fervently expresses her faith in the system, to the point of insisting,