Beyond the scarce figures offered by the island’s government, the real impact of the enclave on the Cuban economy is unknown.

HAVANA TIMES – Gaesa, the Cuban military conglomerate, began supervising a megaproject of a port and development zone in 2011, now headed by former military judge Ana Teresa Igarza Martínez.

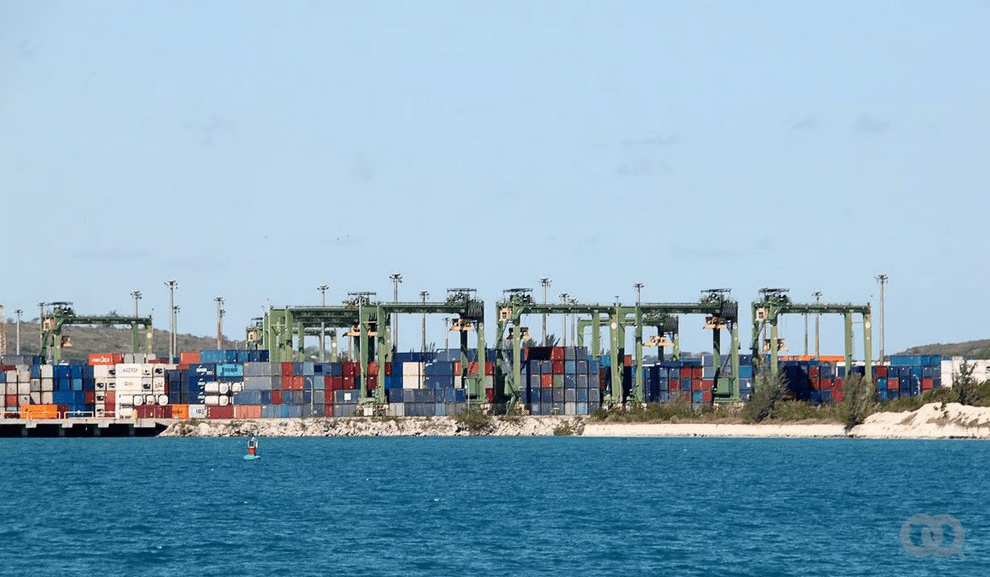

Three years later, then-president Raul Castro inaugurated the container terminal of the Mariel Special Development Zone (ZEDM) in Artemisa province with a tempting promise, to be the main gateway for Cuban foreign trade.

“I must emphasize that this terminal (…) and its geographical location on the route of the main maritime transportation flows in our hemisphere will consolidate its common position as a first-rate logistics platform (…),” Castro stated on January 27, 2014. “This container terminal and the powerful infrastructure that accompanies it are a concrete demonstration of the optimism and confidence with which Cubans look to the socialist and prosperous future of the homeland.”

Promises are one of the best smoke screens that the Communist Party regime has ever put forward. Ten years later, the ZEDM is much less than what was announced. It doesn’t take off. It doesn’t even walk at a somewhat stable pace, and future prospects are uncertain.

But could anything more be expected in a country governed by a political-military elite reluctant to make deep economic changes due to political considerations? Was ZEDM a flawed project from the start?

Initial Investment

According to an investigation by Connectas, the support of Brazil under Lula da Silva (2003-2010, his first two terms) made the construction of ZDEM possible. Part of the resources came from a loan from the public Brazilian Development Bank (Bndes).

Through the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht, the Bndes granted Cuba US $641 million to build the Port of Mariel. The loan was granted through five agreements signed between 2009 and 2013, which included a 25-year term for the Cuban government to repay the debt.

“This project has had significant financing from the Brazilian government on advantageous terms,” acknowledged Raul Castro during the opening of the ZEDM, created by Decree Law 313/2013.

The construction was carried out by Odebrecht, which was later implicated in a gigantic corruption scheme involving several Latin American countries. Cuba is not officially linked to the accusations.

After being elected president in 2018, Jair Bolsonaro ordered an investigation into the Brazilian bank’s loan to Cuba. Bolsonaro stated in January 2022 that loans granted to other countries by his predecessors in the government were “legal,” but he assured that there was “misuse” of public resources, according to an EFE report.

Cuba owes Brazil about $520 million, as reported by Infobae.

The Megaproject that “Didn’t Take Off”

ZDEM was presented from its inception ten years ago as a key project to promote foreign investment, economic diversification, and export promotion. However, it has fallen short of expectations and has attracted only a fraction of the investment needed to boost the island’s economy, generating controversy over its management and effectiveness.

Unlike free trade zones, special development zones have a broader concept and offer benefits not only for manufacturing companies but also for technological inno