What can they expect in 2025?

HAVANA TIMES – Some shouts in Russian followed by a loud bang, woke Yoel on a cool early morning of the Moscow summer. The hostel where he was staying, in the Vidnoe area, south of Moscow, was the epicenter of one of the frequent police raids on places that house migrants. More than 75 Cubans, including women and some minors, mostly in irregular situations, ended up that night in a police station.

“They tore everything apart, they said they were looking for drugs or weapons, I don’t really know. The fact is they took all of us to a station, and we stayed there until the next day, lying on the floor wherever we could. It’s one of the hardest moments I’ve had in Russia,” he recounted.

Yoel, a 32-year-old from Havana, was one of the first to be released. Despite being in Russia illegally since 2021, the stamps in his passport indicated he was apparently “legal.” He arrived, like most Cubans, as a tourist, for which there is a visa exemption agreement between the two countries. Just two months earlier, he had traveled to Armenia to reset the count of allowed days in the territory of the Russian Federation. “Apparently legal,” since, although the current law stipulates that tourists can remain in the country for 90 days in six months, until now, authorities typically did not check prior stays.

Others, who had already exceeded the legal time limit, were detained for a few days but were eventually released with a fine and a deportation order. “We were lucky, after all. I know people who are or have been in detention centers for months, until someone pays for their ticket back to Cuba,” Yoel explains.

Not a Country for Migrants

Things could get worse for irregular foreigners in 2025, including thousands of Cubans, when a new immigration law comes into force. The law was signed by Russian President Vladimir Putin in August after quickly passing through the State Duma (Russian Parliament).

The federal legislation will, among other things, establish a new legal process for the expulsion of immigrants without legal grounds to be in Russian territory. It will authorize law enforcement to deport them without a prior trial, reduce visa-free stay periods to 90 days per year, and restrict certain rights of irregular foreign nationals, such as freedom of movement or changing residence without authorization. They will also be prohibited from driving, marrying, accessing phone lines, opening bank accounts, receiving loans, or transferring money. There will also be tighter control measures from the authorities.

To curb illegal immigration, over 20 new bills prepared by the State Duma’s Migration Policy Commission have been sent to the Supreme Court and the Russian government and are expected to be discussed and approved soon.

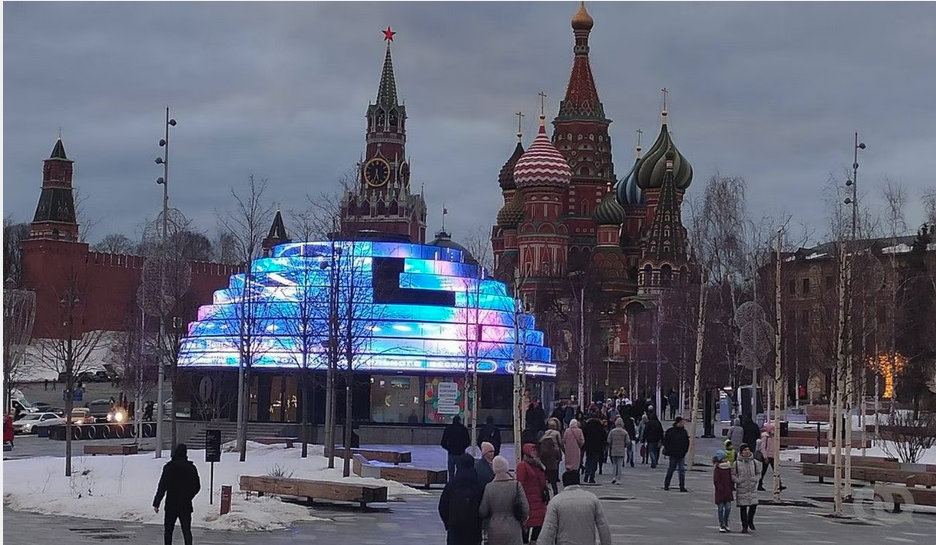

In recent years, there has been an increase in controls, raids, and deportations of migrants. The hostile environment intensified in March after the terrorist attack at the Crocus City Hall concert venue, outside Moscow, which left 145 dead and over 550 injured, and for which Tajik nationals were blamed. This and other incidents, combined with the government’s stance, have led to increased expressions of racism and xenophobia in Russian society.

“The authorities are being strict. Security has increased in the metro, with more police checkpoints to control migrant documentation. If you’re in a taxi, they stop the driver [often a foreigner], ask for documents, and if they see you’re a foreigner, they ask for yours too. I’ve been stopped in my own car for no reason to check my papers,” says Pedro Luis García, a young Cuban with family and Russian citizenship who has lived in Moscow for a decade.

Although controls and raids primarily target Central Asian citizens (from the former Soviet republics), who make up the majority of the foreign population, Cubans are not exempt. Cuban migrants are increasingly a focus of the authorities due to their frequent irregular status and the limited legal avenues for settling.

Pedro, a legal advisor and creator of the YouTube channel “Moscowexpress, Cubans in Moscow,” has been aware of many deportation cases and has noticed a stricter enforcement of laws in recent months. “One of my clients is about to marry a Russian citizen, and she is pregnant. He’s awaiting trial for overstaying by 15 days and is at risk of deportation and a 10-year entry ban.”

This is partly due to the implementation of a digital registry that creates a profile for each foreigner when they enter or leave the country, which remains in the immigration authorities’ database. Moreover, Russia’s Ministry of Digital Development proposed a pilot project for biometric data collection from foreign nationals and those entering the country without a visa, which is set to begin this year.

Thus, “it