Interview with historian Clint Smith

HAVANA TIMES – We feature a special broadcast marking the Juneteenth federal holiday that commemorates the day in 1865 when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, learned of their freedom more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

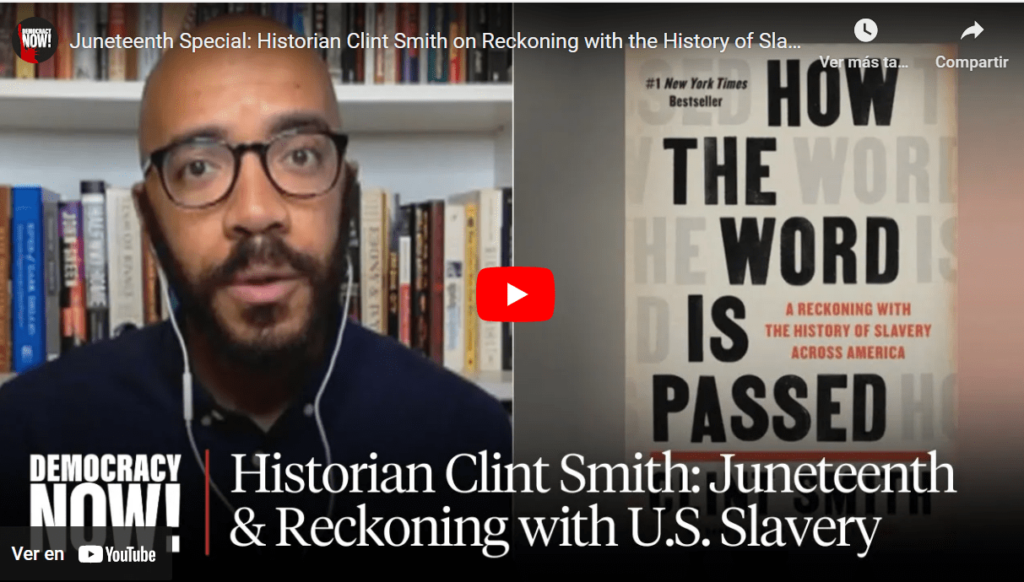

We begin with our 2021 interview with historian Clint Smith, originally aired a day after President Biden signed legislation to make Juneteenth the first new federal holiday since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Smith is the author of How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America.

“When I think of Juneteenth,” Smith says, “that it is this moment in which we mourn the fact that freedom was kept from hundreds of thousands of enslaved people for years and for months after it had been attained by them, and then, at the same time, celebrating the end of one of the most egregious things that this country has ever done.” Smith says he recognizes the federal holiday marking Juneteenth as a symbol, “but it is clearly not enough.”

Transcript

AMY GOODMAN: Today, a Democracy Now! special on this, the newly created Juneteenth federal holiday, which marks the end of slavery in the United States. The Juneteenth commemoration dates back to the last days of the Civil War, when Union soldiers landed in Galveston, Texas — it was June 19th, 1865 — with news that the war had ended, and enslaved people learned they were freed. It was two-and-a-half years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

In 2021, President Biden signed legislation to make Juneteenth the first new federal holiday since Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. The day after Biden signed the legislation, I spoke to the writer and poet Clint Smith, author of How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. I began by asking him about traveling to Galveston, Texas, and his feelings on Juneeteenth becoming a federal holiday.

CLINT SMITH: As you mentioned, I went to Galveston, Texas. I’ve been writing this book for four years, and I went two years ago. And it was marking the 40th anniversary of when Texas had made Juneteenth a state holiday. And it was the Al Edwards Prayer Breakfast. The late Al Edwards Sr. is the state legislator, Black state legislator, who made possible and advocated for the legislation that turned Juneteenth into a holiday, a state holiday in Texas.

And so I went, in part, because I wanted to spend time with people who were the actual descendants of those who had been freed by General Gordon Granger’s General Order No. 3. And it was a really remarkable moment, because I was in this place, on this island, on this land, with people for whom Juneteenth was not an abstraction. It was not a performance. It was not merely a symbol. It was part of their tradition. It was part of their lineage. It was an heirloom that had been passed down, that had made their lives possible. And so, I think I gained a more intimate sense of what that holiday meant.

And to sort of broaden, broaden out more generally, you spoke to how it was more than two-and-a-half years after the Emancipation Proclamation, and it was an additional two months after General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, effectively ending the Civil War. So it wasn’t only two years after the Emancipation Proclamation; it was an additional two months after the Civil War was effectively over.

And so, for me, when I think of Juneteenth, part of what I think about is the both/andedness of it, that it is this moment in which we mourn the fact that freedom was kept from hundreds of thousands of enslaved people for years and for months after it had been attained by them, and then, at the same time, celebrating the end of one of the most egregious things that this country has ever done.

And I think what we’re experiencing right now is a sort of marathon of cognitive dissonance, in the way that is reflective of the Black experience as a whole, because we are in a moment where we have the first new federal holiday in over 40 years and a moment that is important to celebrate, the Juneteenth, and to celebrate the end of slavery and to have it recognized as a national holiday, and at the same time that that is happening, we have a state-sanctioned effort across state legislatures across the country that is attempting to prevent teachers from teaching the very thing that helps young people understand the context from which Juneteenth emerges.

And so, I think that we recognize that, as a symbol, Juneteenth is not — that it matters, that it is important, but it is clearly not enough. And I think the fact that Juneteenth has happened is reflective of a shift in our public consciousness, but also of the work that Black Texans and Black people across this country have done for decades to make this moment possible.

AMY GOODMAN: And can you explain more what happened in Galveston in 1865 and, even as you point out, what the Emancipation Proclamation actually did two-and-a-half years before?

CLINT SMITH: Right. So, the Emancipation Proclamation is often a widely misunderstood document. So, it did not, sort of wholesale, free the enslaved people throughout the Union. It did not free enslaved people in the Union. In fact, there were several border states that were part of the Union that continued to keep their enslaved laborers, states like Kentucky, states like Delaware, states like Missouri. And what it did was it was a military edict that was attempting to free enslaved people in Confederate territory. But the only way that that edict would be enforced is if Union soldiers went and took that territory.

And so, part of what many enslavers realized — and realized correctly — was that Texas would be one of the last frontiers that Union soldiers would be able to come in and force the Emancipation Proclamation — if they ever made it there in the first place, because this was two years prior to the end of the Civil War. And so, you had enslavers from Virginia and from North Carolina and from all of these states in the upper South who brought their enslaved laborers and relocated to Texas, in ways that increased the population of enslaved people in Texas by the tens of thousands.

And so, when Gordon Granger comes to Texas, he is making clear and letting people know that the Emancipation Proclamation had been enacted, in ways that because of the topography of Texas and because of how spread out and rural and far apart from different ecosystems of information many people were, a lot of enslaved people didn’t know that the Emancipation Proclamation had happened. And some didn’t even know that General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox two months prior. And so, part of what this is doing is making clear to the 250,000 enslaved people in Texas that they had actually been granted freedom two-an