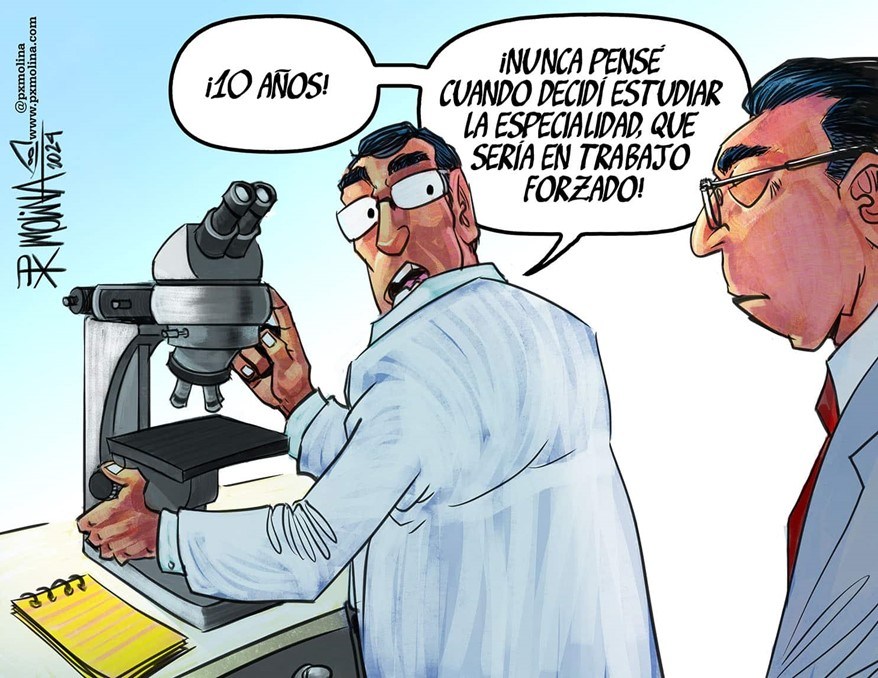

Either spend ten years working for the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health, or “buy back your freedom” for the sum of US $61,700. That’s the dark panorama facing the new generation of Nicaraguan doctors who want to specialize.

By Elthon Rivera Cruz (Confidencial)

HAVANA TIMES – The famous philosopher Plato coined a phrase which – given the current situation – now resounds in the mind of the health professionals. For those of us who dedicate our efforts to bettering people’s health, his assertion recalls the nobility and dedication with which we should be doing our work. The phrase goes: “Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love of humanity.”

Plato’s words hold great truth, since the art and science of healing our neighbor is an act of love for life itself. However, for this to be manifested, one fundamental characteristic is needed: having humanity. Not only in the sense of the person’s own nature, but also from the point of view of the emotions – those elements that allow us to demonstrate compassion, solidarity and empathy. Lacking these, you can’t love medicine, since there’s no love for humanity itself.

Without framing this reflection in excessive romanticism about the profession, it’s understandable then that those of us who take the step of entering the service of medicine accept that we’ll be dedicating a large part of our lives to our preparation. It’s no secret to anyone that to achieve the crown of a medical degree requires around six years of study in most of the world’s countries. In countries like Nicaragua, we must add on two years of social service, and later between three and five years of specialization. That means that a specialist in a medical field has spent at least ten years preparing, and depending on their profile, it could be more. A large part of our youth is lost in the universities and hospitals, not to mention the entire process of continuous professional education we must engage in, to stay abreast of the new advances and problems in health.

It’s fair to say, then, that after so many years, these doctors have earned the freedom to decide the manner and the place in which each one wants to exercise their career. We should also take into consideration the fact that all those years of preparation aren’t well remunerated, and their pay is nowhere near proportionate to the workload assigned to the residents in each specialty. It’s likewise no secret that in Nicaragua the health profession is seriously exploited and mistreated.

Nonetheless, now the Sandinista government led by Daniel Ortega and his partner has taken one more step in their policy of repression against all the social and professional sectors – they’ve imposed a new rule that doctors wishing to enter a residency program must sign a contract obligating them to serve up to ten years i