the government’s response to the protests of March 17th

HAVANA TIMES – On Sunday, March 17, 2024, images of protests in Santiago de Cuba and later in Bayamo surprised Cubans inside and outside the island once again. Surprise continues to be part of the immediate reaction to popular demonstrations; a response probably more associated with the moment in which they occur than with the fact of their occurrence itself. Despite systematic repression, massive exodus, and the inertia sustaining the regime, it was somewhat expected that the worsening living conditions would lead to new protests (in the absence of another viable channel to express discontent and seize the right to participate in the country’s political life).

After July 11, 2021 (11J), the Cuban Government opted for regular repression, using laws that would guarantee further closure of the space for civic struggle, and for propaganda to repeatedly return to its imagery, highlighting the deep disconnection and disinterest in the lives of ordinary people. Nevertheless, the Cuban powers that be should not have been completely surprised by the emergence of popular discontent in the form of spontaneous demonstrations. It is foreseeable, even for an alienated Government, that the worsening economic crisis would result in the eruption of discontent.

The possible evidence that it was not the type of surprise that mobilized the crème of power on 11J, was the response that some media and state voices gave during the first hours. Instead of the agitated response that in 2021 called “the revolutionaries to take to the streets” —mostly read as a call to civil confrontation—, what happened on March 17 and the following day was an effort at normalization.

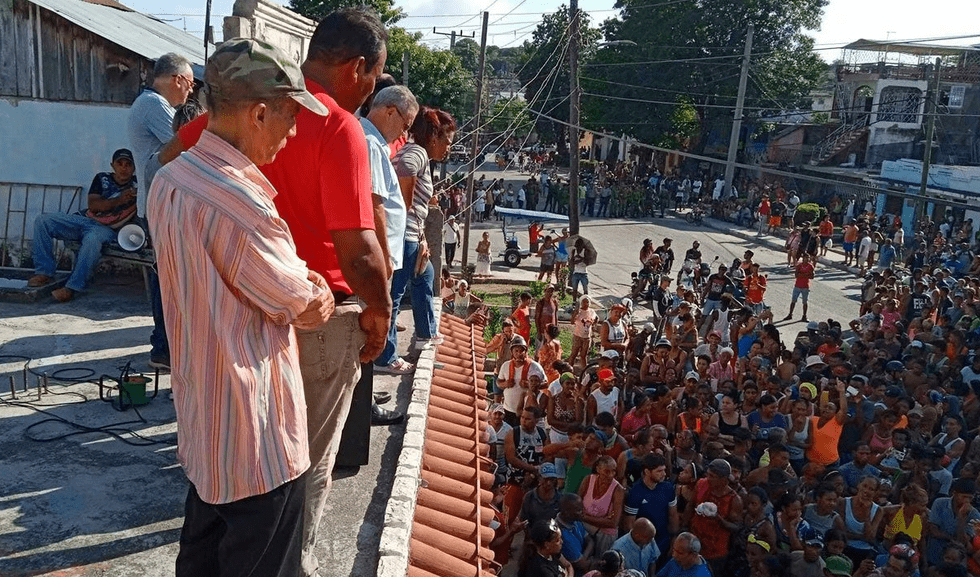

According to Cubadebate —which reproduced a fragment of the original thread by El Necio (as the pro-government communicator Pedro Jorge Velázquez presents himself) on X—, “several people took to the streets and a popular demonstration occurred” in reaction to the long hours of power outages and “other situations derived from the current economic crisis.” There were, in addition to requests for food and electricity, chants of “Patria y Vida,” (Homeland and life) but “were not followed by the majority,” according to official sources.

The government description leads to a series of clarifications. The police showed up at the scene to prevent violent events (“they are only guarding the demonstration and directly dialoguing with the citizens”). Authorities also showed up “to dialogue with the population and attend to their demands.” That is, a “normalized” view of the protest —although it is a vague description, it is recognized as such—, people express their dissatisfaction, the police guard and prevent any violence, and the authorities engage in dialogue.

However, the apparent change in communicative approach should not be read as a change in the general strategy for dealing with protests. It is possible that the “normalization” responds to a change in tone because the original thread on X, replicated by Cubadebate, comes from an influencer spokesperson for the Cuban Government (El Necio) who does not resort to the typical rhetoric of state media. Moreover, the gap between the influencers who speak for the Government and the communication channels of the Cuban State is too small to notice different positions in the difference in tones. Therefore, the new approach should be considered, rather, as a communicative strategy that adds to th